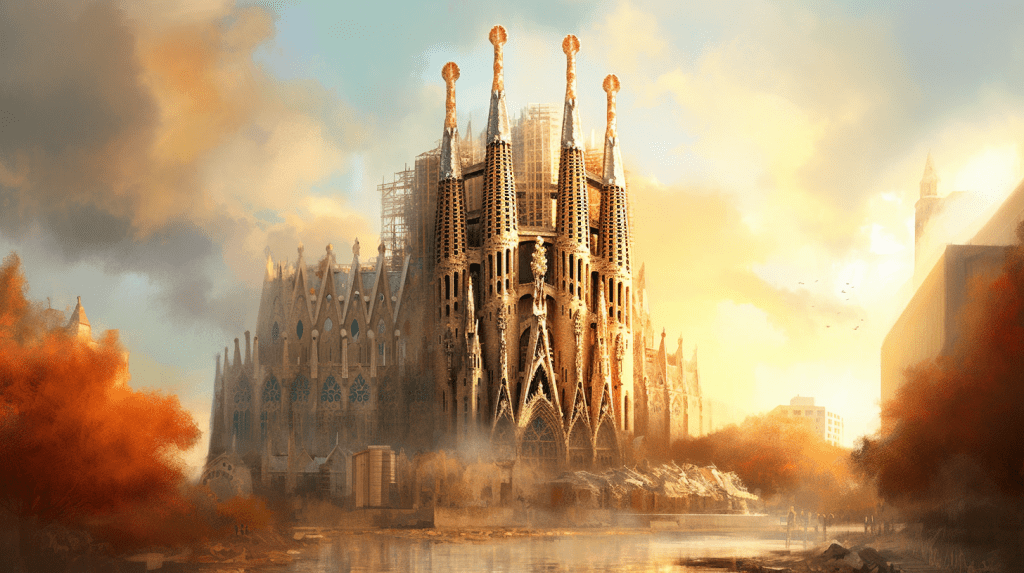

A few months ago, I had the privilege of visiting Antoni Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia in Barcelona. The basilica is a remarkable project by any metric, but the part I found most impressive was not the building’s daring combination of styles or its brilliant engineering, but the degree to which the (nearly) final product has remained faithful to Gaudi’s original vision after more than 140 years of construction.

Radical mid-assembly design modifications are rare among contemporary buildings which come together quickly, but they happen all the time on projects that take multiple generations to finish. This creates a serious problem for designers who wish to protect the integrity of their intent on work conceived with long-term ambition.

St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City, for example, was redesigned by at least six different architects before it was finally declared complete. Most of Europe’s great cathedrals followed similar trajectories.

So what made it possible for the Sagrada Familia to escape such a fate? How did Gaudi ensure that his vision would prevail despite his inevitable future absence?

He did it by recognizing that long gestation periods can have a big impact on a project’s odds of success, and that a key part of the design process on long-term work must involve creating a plan to maximize lock-in while the original visionary is still around.

Although no designer is in a position to guarantee the outcome of projects with century-spanning timeframes, it’s always possible to make strategic choices early that vastly improve their chances of being realized according to plan.

Gaudi and his team’s key stroke of genius in this regard was to specify that the building would be built in an unconventional order. Rather than working on everything at once, the decision was made to focus almost all initial resources on erecting the nativity facade while Gaudi was still available to supervise.

Although Gaudi only lived to see about 20% of the Sagrada Familia completed, ensuring that one of the building’s three key facades was built to full height secured a few things that would prove critical for the project’s future.

First, building tall from the outset allowed the structure to attain an instant presence on the city’s skyline, thereby establishing an integral link between the Sagrada Familia and the municipal identity of the place in which it stands.

Second, completing the nativity facade to a final stage of resolution provided a strong and irreversible statement about the project’s highly distinct intended aesthetic. Getting this built down to the smallest ornamental details made it almost impossible for a subsequent head architect to credibly complete other sections of the building according to the conventional Gothic sensibilities that Gaudi was trying to escape.

Third, by pouring all initial resources into just one facade, Gaudi ensured that the project would require substantial additional investment before a congregation could make use of the structure for religious services. Had he taken a more standard approach and provided a usable space early in construction, it’s possible motivation to complete the building would have been much reduced. After all, it’s easy to imagine people asking why there should be millions more spent on a facility that already gets the job done. The Westminster Cathedral in London is a great example of a comparable building that fell into just such a trap. To this day its interior remains largely incomplete with no sign of imminent change.

Finally, by using seed funds in a way that created something worth looking at from the beginning, Gaudi enabled the building’s construction to become a self-sustaining attraction powered by contributions from proud locals and curious tourists alike.

In an era of big challenges and bigger opportunities, I think projects guaranteed to outlive us are the only kind that can be considered sufficiently ambitious. As Gaudi demonstrates, succeeding as designers engaged in this kind of work requires that we consider the difficulties implied by a project’s gestation period with equal attention to the way it looks or performs. Although the tactics Gaudi employed with the Sagrada Familia won’t be applicable in many contexts, I think useful equivalents can probably be devised for projects of all kinds.

Design is not just about aesthetics or functionality, it’s about defining what we hope to achieve and figuring out the whole plan for making it happen. While the long-term future will always be uncertain, adopting a thoughtful and holistic approach can go a long way toward improving our likelihood of success. If we manage to do that, I think we can rest satisfied that we’ve done our jobs well — regardless of how things may ultimately turn out. Either way it goes, if we’ve taken on something with the magnitude of ambition that our present situation calls for, we won’t be here long enough to find out. I think that fact fortunately offers the possibility for us to retain the kind of emotional resiliency that such endeavours demand.