Many designers try to solve problems by changing how people behave. On the surface that makes sense. We wouldn’t have litter if you could stop people from throwing trash on the ground.

The challenge, as Buckminster Fuller has described, is that people don’t respond well to being told what to do. We can make rules, but at scale they can be hard to enforce without voluntary enrolment. Littering fines haven’t prevented litter.

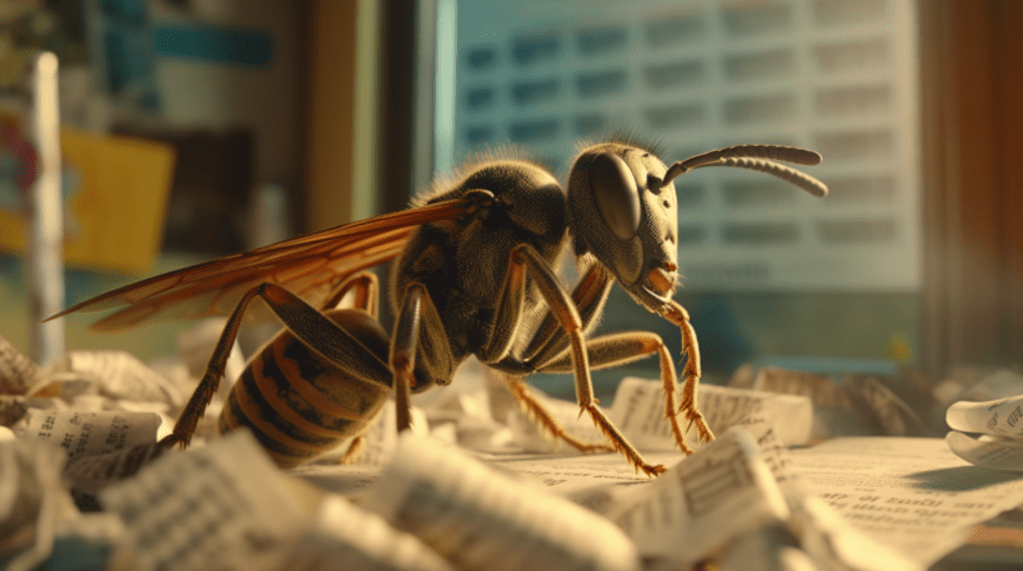

Fuller’s proposed alternative to fighting human nature (which he views as fixed) is to focus instead on reforming the environment in which we live. To use his example, if a wasp flies into your kitchen, you can try to bat it out through the crack of an open window, but it might be more effective to switch off the lights and cover the fixed panes of glass with some newspaper. Do that, and the wasp will leave on its own in a minute.

What Fuller’s analogy overlooks is that unlike wasps, the behaviour of humans isn’t baked in. Society’s values and preferences have moved a long way from where they were a century ago. The culture evolves over time. People can and do change — and it’s often of their own accord.

You can’t prevent littering with fines, and it’s impractical to “reform the environment” by placing garbage cans every 6 feet, but littering is virtually guaranteed to subside if a generation of people are taught to embrace an attitude of stewardship.

Cultural shift isn’t something most designers think about as a potential solution to the problems they engage with, but in many cases it’s the best answer available. Regardless of the kind of design we practice, our toolboxes would be greatly expanded by studying how cultural shift has been spurred by our predecessors who have found a way to create change while avoiding getting stung.